Leavey Professors Explore How Natural Disasters Can Increase Sustainable Consumption Among Those Who Resist It

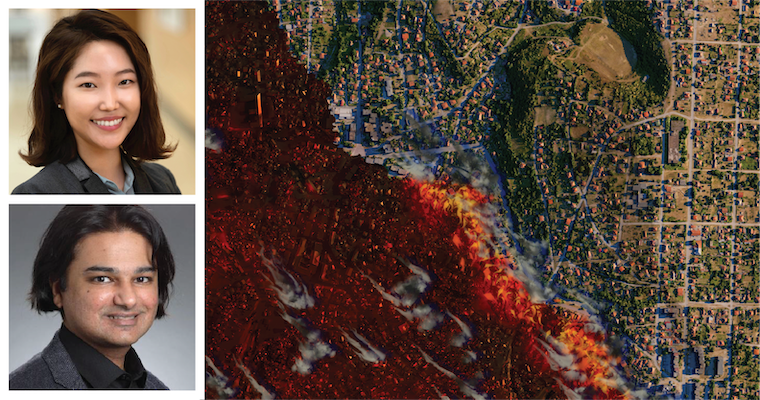

As climate change continues to accelerate, exacerbating natural disasters around the world, the call for sustainable action grows louder. However, a significant challenge remains: getting individuals who have traditionally resisted sustainability, particularly those on the political right, to embrace environmentally friendly behaviors. New research by Leavey School of Business marketing professors Rebecca Chae and Rafay Siddiqui explores a surprising factor that could have an effect on individuals' sustainable consumption: vulnerability to natural disasters.

Residents of California, the state that experiences the most natural disasters in the United States, Chae and Siddiqui came together with a shared interest in sustainability and questions about how characteristics like political affiliation and regional location differences can cause some groups to be more interested in sustainability than others.

Their research, Vulnerability to natural disasters and sustainable consumption: Unraveling political and regional differences, which covers four regions and 24 countries, finds that for individuals with right-wing political leanings in Western societies like Western Europe, Israel, and the United States, an increased vulnerability to natural disasters like wildfires, floods, or storms led to a marked increase in intentions to adopt sustainable consumption practices. Conversely, the study finds that leftists, who already tend to embrace sustainable behavior, don’t show as significant an increase in sustainable intentions despite their growing vulnerability to climate events.

Siddiqui explains that “for right-leaning individuals, the expectation of being directly impacted by climate change could override longstanding resistance to sustainability. However, for those already committed to sustainability, the direct threat of climate change doesn’t necessarily push them to do more.”

Building off these initial findings, the authors launched a quasi-experiment to test the potential of an intervention that used localized messaging about recent natural disasters. This tactic proved effective in pushing right leaning individuals toward sustainable consumption, highlighting the necessity of tailored marketing strategies, especially for highly polarized topics like sustainability.

“People’s attention spans are limited. After experiencing a disaster, they might forget, especially if they are not directly impacted by it, which is where targeted intervention might become effective,” Chae adds. “Let’s say that the national news covers the recent wildfires that happened in California. The more that the media highlights the impacted area at a state level instead of just the local community, the more of an impact it will have statewide on increasing the political right’s intentions to consume sustainable products. Communicators can alter the framing of the location to make people feel like they’re closer to the place where the natural disaster happened, even if it’s in a different city, for example.”

As the effects of climate change become more apparent, the need for broad-based support for sustainable practices is more urgent than ever. Chae and Siddiqui’s research offers valuable lessons for both environmental advocates and marketers striving to inspire positive change. By making climate risks feel personal and close to one’s locality, it's possible to shift even the most resistant political groups toward sustainable behaviors. In the face of accelerating climate change, we can all play a part in fostering a culture of sustainability, not by pushing people to act out of guilt or fear, but by connecting them to the real, immediate consequences of inaction.

Chae and Siddiqui hope to build on this research and encourage future research to continue studying the impact of political ideology on sustainable consumption and to identify interventions that can bring more lasting change in people’s sustainable consumption.