May 24 - July 2, 2021

Virtual Exhibition

Loneliness Barefaced seeks to connect art to loneliness and therefore the pandemic. As we live through the COVID-19 pandemic, loneliness and social isolation have become omnipresent topics. We have lost the normalcy of human connection to sheltering-in-place and stay-at-home-orders (Berg-Weger 2020). As result, loneliness has been significantly higher than normal this past year (Killgore 2020). A public health study found that loneliness was the main risk factor for depression and anxiety during the Covid pandemic (Palgi 2020). Fortunately, it has also been proven that loneliness is a necessary component of creativity, as an individual requires solitude to create a genuine work of self-expression (Tick 2008). Therefore, it is essential to understand loneliness through art, as it helps us navigate our own identity during this difficult time. By connecting our topic to loneliness in reference to the pandemic, we hope to give museum-goers a unifying experience, in which they can safely share their contexts and opinions.

Ansel Adams, Yosemite Falls, Spring, Yosemite National Park, California, 1983, gelatin silver print, de Saisset Museum permanent collection, Santa Clara University, 6.337.1986

In this photograph from 1983, we see the beauty of Yosemite National Park. Here, the 2,425 foot waterfall, momentous in size, stands as a reminder of the overwhelming power of nature. In our case, it mirrors the effect the pandemic has had on the world’s population. Its massive power reminds us how small we are, and of how lonely it can be to feel so small. The focus upward, furthermore, reminds one of his or her insignificance. This idea also mirrors the events of Covid. His work represents a diverse collection of landscapes, the same way our campus represents a diverse collection of faces.

This work reminds us of existential crisis, a formative power in the pandemic time. The waterfall is a powerful indicator that, from a certain perspective, nothing we do has any meaning. Since a waterfall stays largely unchanged for centuries in its constant flow, we can see that noticeable changes take place over extended periods. Similarly, the pandemic has brought about similar themes since many individuals feel like they are treading water. They are unable to interact with others due to social distancing guidelines. Thus, we realize that the existential crisis, which is perhaps sparked by loneliness is an essential characteristic of art. In a most simplistic sense, landscape photography serves the function of exposing viewers to the awesome.

Laura Gilpin, Navaho Sacred Mountain of the East, 1953, gelatin silver print, de Saisset Museum permanent collection, Santa Clara University, Focus Gallery Collection, Helen Johnson Bequest, 6.33.1989

In this photograph, Gilpin intentionally juxtaposes cartography with an immersive understanding of landscape. Navaho Sacred Mountain of the East drives home the fact that physical distancing stimulates the feeling of loneliness. Perhaps obvious, yet somehow often overlooked, mountains in the distance look unreachable. This physical space between the viewer and the mountains in the image conveys a sense of loneliness and separation. And though we can see an ending, real or conceptual, our brains nonetheless face the reality that this place will be difficult to reach. An end to isolation and its loneliness feels, to many, just as far as the mountains in Gilpin’s photograph.

However, there is also a hopeful message here. As an enthusiastic advocate of the Navajo, Gilpin’s work was not always received clearly by Euramerican audiences (Siddons). She forged her own path and stood up for the underrepresented. Laura Gilpin reminds us that there are people who will stick up for the unheard voices. In Covid, when disparities in socioeconomic standing are ever more potent (health is now an even more acute factor), people will fight for those in need. As we gaze at the distant mountains in Navajo Sacred Mountain of the East, we are reminded that we needn’t do it alone. Photography, here, serves as a metaphor for the journey. Perhaps no other art form puts things into perspective (as it were) more accurately.

Note: Gilpin's original title for this photograph utilizes the spelling "Navaho."

Mark Klett, Camp 3 at Lake Powell, 1984, gelatin silver print, de Saisset Museum permanent collection, Santa Clara University, Gift of David B. Devine, 1991.2.6

Here, the shadows of the rocks speak of dark, overwhelming ethos. It is expert work: Mark Klett was a photographer with the geological survey. This work focuses on the interaction of the human with the landscape and raises questions about time, change, and perception. The isolation of the elements in the photos reminds one of how many of us, though surrounded by friends or family members, have felt alone during the last year. The rock outcropping in the middle takes center stage as if to say “here I am.”

Camp 3 brings forth an immediate question: what is the significance, meaning, and implication of surrounding emptiness? What does it mean to be surrounded by nothing? A simple answer: what is in perspective stands out more. In Camp 3, the objects and rock stand out like a sore thumb. In the same way, the lonely, quarantining individual stands out in her or his own universe. Many of us are spending much of our time alone. Because of a lack of surrounding variables, the immediate situation seems more dire. In Camp 3, the central rock and its shadow seem omnipotent. So do the mental circumstances of the lonely.

We draw a parallel between the choreography of photography and the functions of the psyche: as stated, while surrounded by emptiness, things stick out. And many of us have been surrounded by emptiness these last few months. Mark Klett was deeply interested in the relationship between time and change throughout much of his work. His photographs of Camp 3 are no exception to this theme. Loneliness during the pandemic is largely similar to his theme of change and time since people are learning to adapt to this prolonged state of loneliness where our perception of time and space alters our views on our lives prior to this global event (Klett).

Dugan Aguilar, Stone Mother, Pyramid Lake, 1991, gelatin silver print, de Saisset Museum permanent collection, Santa Clara University, work selected by students in SCU Professor Kate Morris' winter 2007 class, ARTH 142: Native American Art: Special Topics. Funds for this purchase were made possible by SCU's Center for Multicultural Learning, 2007.3.5

Dugan Aguilar (Mountain Maidu/Pit River/Walker River Paiute) was a notable Native Californian photographer. What, then, must it feel like to be someone who exists outside of the groups that have dominated photography for the majority of its history? And the stone mother speaks to this. She is alone, looking away in silent contemplation.

Similarly, much can be said about the peripheral components of the image. The granular rock, for example. Its lines form contours in the foreground of the photograph. These contours dominate our focus; the mother stands as a figure in the distance. And what of her body language? The mother looks away at the distance, seemingly unaware of the camera’s lens. It’s as though she’s there in her element paying little heed to the photographer. She has a somewhat lonely stance. The mountains in the distance also indicate a dynamic of perspective. We see the rocky surface in the foreground, then the mother, and then the sky and mountains.

Unknown, Mission District - Fire Trap, San Francisco, Calif., 1936, Black and white photograph, de Saisset Museum permanent collection, Santa Clara University, Purchased from Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA, NDA.6.706

The Mission District is one of San Francisco’s most-visited neighborhoods. It houses boutiques, restaurants, vibrant murals, and Mission Dolores, one of the oldest icons of the city. This area is normally filled with life and culture. To see it boarded up tells viewers that the everyday hustle and bustle is not occurring in this photo. Visually, this photo shows a lack of life. The photographer was interested in the geometry of what he or she was looking at. The boards create small groups of lines next to each other calling to each other giving a sense of dimension when there appears to be none.

Mission District, artist unknown, raises interesting questions about the problem of belonging, of uniformity. What does it mean for the lines of wooden boards, as in Mission District, to stand vertically and identically, seemingly without identity? Simply this: when each object is identical (in this case, the vertical boards) nothing stands out. Uniformity often lacks vibrancy. We are all trapped within the confines of the pandemic quarantine, yet few are comfortable. There is, as a result, less room to stand out, and to be heard. None of these boards speaks particularly to the observer; as an aggregate, however, they form a cohesive image. During this difficult time, the same question arises. In the “grand scheme of things,” are we individuals, or just “bricks in the wall?” Certainly, the composite of human beings forms a beautiful canvas of color, sound, and impression. The composite of boards in Mission District forms a similar canvas. Yet who would care to look at an individual board?

Perhaps this photograph suggests a way out of loneliness: a contribution to something greater than oneself. Though bleak as an individual, one adds greatly to the stream of life through his or her contributions. It seems that by finding meaning in the collective, one finds meaning in oneself. Thus, the loneliness of being an individual board, insignificant and pointless, transforms into the purpose of bringing life to a greater picture: the canvas of human achievement. Mission District is a visual delineation of this concept.

Unknown, Erosion destroyed hillside, 1/1/1938, 1938, black and white photograph, de Saisset Museum permanent collection, Santa Clara University, Purchased from Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA, NDA.6.682

Erosion contains many different elements throughout the photograph. The main theme that we see here is, again, that the photograph evokes loneliness. For example, many of the trees in the landscape lack leaves and the black and white medium of the photograph gives it a desolate feeling. The black and white texture initially makes us feel desolate, and then goes on to make the viewer feel more alienated after looking at it longer.

There is also an overturned chair next to the small cabin in the bottom right of the image, which gives the impression that no one has been around for some time. An alternative idea is that the person who was there may have left abruptly for some particular reason. We do not know why, but can interpret or imagine what may have happened. The sole presence of the chair furthered the idea of both isolation and loneliness, but perhaps at the same time also gives a sense of hope or possible return. There is a chair there so there must have been a person there at some point too. Will they be coming back? Or are they running or hiding from something?

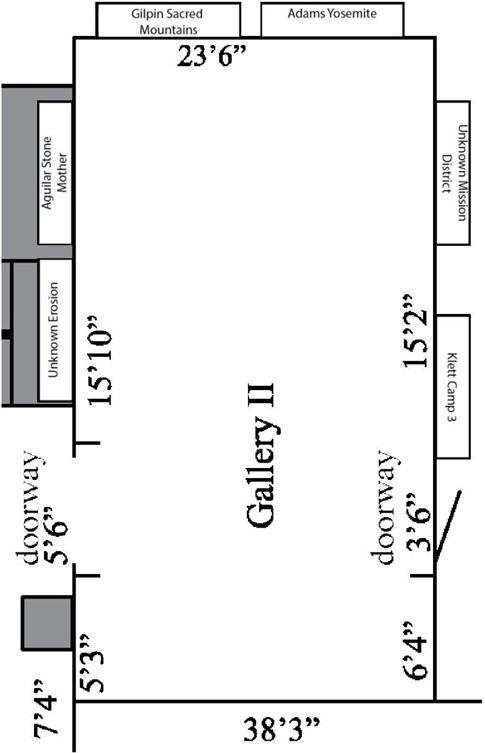

Adams’ Yosemite & Gilpin’s Sacred Mountain

We paired these photographs together for several reasons. Firstly, they both demonstrate the awesome power of nature in distance and force. Furthermore, they point towards the largeness of nature relative to that of the person.. They relate to loneliness in their interpretation of the existential nature of meaning (because of nature’s largeness).

Aguilar’s Stone Mother & Erosion by unknown artist

We paired Stone Mother and Erosion together because they are both relatively plain and also landscape photographs. They feature barren land in a dark setting and some of the patterns on the rock look similar. This connects to the exhibition essay because the overall bleak nature of the landscape alludes to the similarities in both pictures. Additionally, there is a lonely and isolated element in each photograph. The patterns and dull elements of the photograph allow it to feel desolate and alone.

Mission District & Klett’s Camp 3

We paired these photos next to each other for their shared visual appeal of stillness and minimalism. Our other photos have much more texture diversity in their compositions while these photos have very little to look at. They feel akin to blank canvases. Additionally, having little context allows viewers to project more of themselves into the scene. We hope that viewers experience elements of meditation in this individual experience of placing oneself in an image alone and achieve a sense of peace from this openness.