Guarding a Precious Commodity

For their capstone work, bioengineering seniors Nina Morrison, Samantha O’Connor, and Callie Weber wanted to tackle a brand-new project, from the ground up. “We knew it would entail a lot more effort, researching and understanding the field before even starting on the engineering, but also knew we’d rather spend more time if it is something we’re passionate about,” said Callie. Passionate, they are; and more work, they got!

Advised by Unyoung (Ashley) Kim, associate professor and expert in integrated microfluidic systems for biotechnologies, the team has designed a low-cost paper-based sensor to detect the presence of E. coli in human breast milk donated to breast milk banks. Their aim is to ensure post-pasteurization safety in developing countries, where traditional lab culturing methods are unavailable. Nina explains that a podcast about breast milk donation opened their eyes to the need for this product: “A mother who was unable to breastfeed but had an infant who was allergic to formula told a desperate story of looking on the black market and Craigslist for milk for her baby. That inspired us to see how we could improve technology and milk banking.”

Putting their inspiration into action, the trio sought the help of public health students Karen Mac and Maya Tromburg, and the advice of Michele Parker, adjunct lecturer for biology and public health science and advisor of SCU’s Engineering World Health student organization, to get a fuller picture of how their device could best benefit mothers in need. “In the fall quarter we met each week to share information and develop a solid understanding of the breast milk field. We’ve also been advised by Mothers’ Milk Bank in San Jose, and had an exploratory call with PATH, a nonprofit in Seattle that promotes milk banking globally, to learn about the needs of milk banks, mothers, and society as a whole,” said Callie.

Once they had a clearer picture of the field, they got to work designing what they now call Milk Guard. “We wanted it to be low-cost and frugal to implement. Using paper as our platform instead of PDMS substrate microfluidics, as would normally be used in this type of project, keeps cost down,” said Samantha. Basically, the test works like this: the paper on top of which lie biomolecules encased in silica gel (to retain stabilization) is dipped into a pre-treated sample of human breast milk; if E. coli is present, the paper will turn blue. Nina reports that making the gels and moving the detection method onto a paper platform has kept the trio busy over the past two quarters.

It’s been time well spent. The team was selected to present their Social Enterprise Pitch at the Global Health Conference at Yale University in April, sharing their sensor with—and gaining insight from—a panel of experts in a room full of maternal health authorities. In June, Callie and Karen will travel to Mumbai, India, to share their device with LTMGH (Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital), locally known as Sion Hospital. For now, they are working to validate their results locally with Mothers’ Milk Bank, which currently spends $4,000 per month outsourcing the bacteria culturing process.

Though they’ve come so far with their project this year, there’s much to be done. “We wanted to start a project from scratch,” Samantha said, “and we’ve grown so much through doing the research, making connections, and developing a prototype. This experience will be so helpful to us as we start our careers, but we really want future senior design teams to take it even further.” Nina agrees: “We hope that this is just the very starting point, that other groups will lower the limit of detection and add testing for other contaminants to make the sensor more robust. But this year, this has been our baby, and it’s given us a lot of confidence in ourselves.”

More on the project: breastmilksensor.org

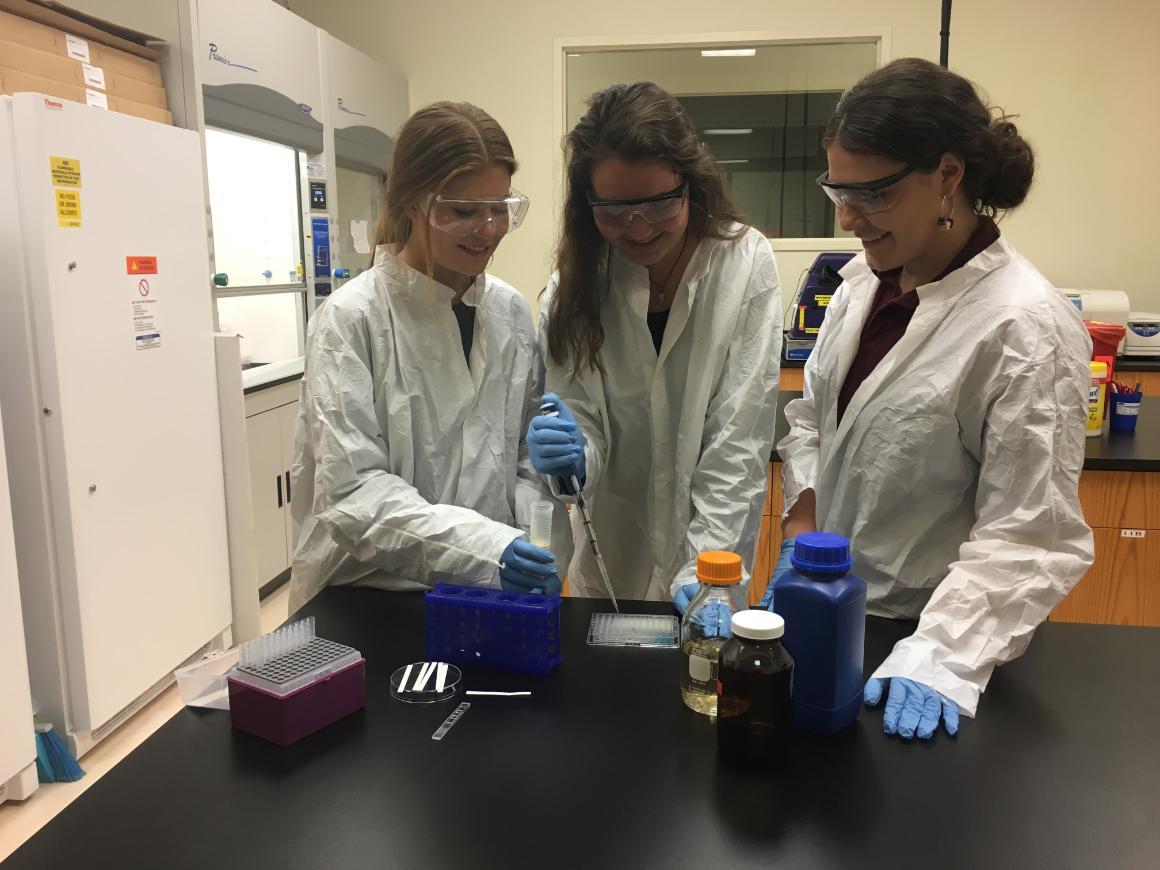

(From left) Samantha O’Connor, Callie Weber, and Nina Morrison at work on Milk Guard, a low-cost breast milk contaminant sensor. Photo: Heidi Williams