Prepared by:

Julia A Scott, Ph.D, Director of Brain and Memory Care Lab, Bioengineering, Santa Clara University; Council Lead, MedXRSI

Bhanujeet Chaudhary, Former Chief of Staff, XRSI

Aryan Bagade, MS, Computer Science and Engineering, Santa Clara University

Originally presented at PRIM&R 2024 Annual Meeting

Description

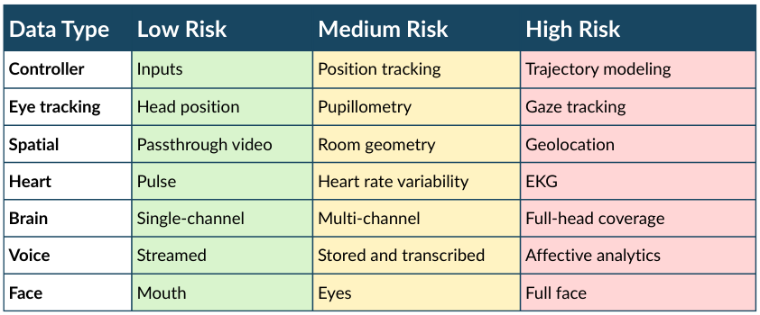

Immersive technologies are a potent research tool. Spatial and embodied technologies (e.g. virtual reality, brain-computer-interfaces) take the study of human behavior to an arena that is not bound by typical norms. It introduces novel types of experiences and data (Table). In addition, containment of participant data is no longer as simple as storage on a secured hard drive, design of a safe experiment must take into account psychological effects of embodiment, and, in some scenarios, data cannot be reasonably de-identified. Consequently, data management practices and psychological safety need to be updated in the review process. These structured case studies and resources will inform participants of the risks associated with immersive technologies and provide guidance on safeguards to support productive human subjects research in this field.

Table 1. Body data captured by spatial technologies

Figure with the title of RISKS: Assessment Framework. In each panel the risk type is named as follows: Health and Safety Risks, Social and Ethical Risks, Content and Media related Risks, Data Protection and Privacy Risks, Autonomy and Cognitive Sovereignty Risks, Cybersecurity Risks, Financial Risks, Legal and Regulatory Risks, Emergent AI Risks. Source: Scott, Chaudhary, Bagade, 2024.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the risks associated with using immersive technologies in human subjects research

- Understand the challenges of data containment and de-identification when using immersive technologies

- Learn how to apply updated data management practices and psychological safety measures in the review process for studies involving immersive technologies

- Develop safeguards to support productive and ethical human subjects research using immersive technologies

Figure 1. Risk categories associated with spatial technologies

Figure with the title of RISKS: Assessment Framework. In each panel the risk type is named as follows: Health and Safety Risks, Social and Ethical Risks, Content and Media related Risks, Data Protection and Privacy Risks, Autonomy and Cognitive Sovereignty Risks, Cybersecurity Risks, Financial Risks, Legal and Regulatory Risks, Emergent AI Risks. Source: Scott, Chaudhary, Bagade, 2024.

How to use this guide

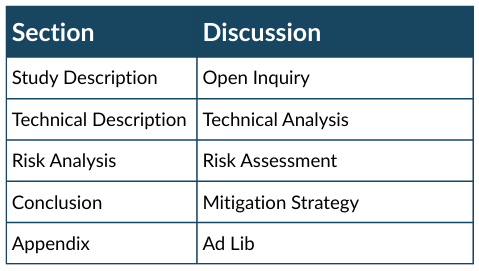

Participants work in small groups (5-8 recommended) through structured case studies--Study Description, Technical Background, Risk Analysis, Conclusion (Table). The case studies are divided into four analytical domains, with 15 minutes for each--Open Inquiry, Technical Analysis, Risk Assessment, Mitigation Strategy, and discussed for a total of 60 minutes. Groups complete each step in sequences. In each block, participants read the section individually (about five minutes). The information fom the active section, previous section(s), and appendix may be considered. Each section has specific, targeted questions on the information provided. The information fom the active section, previous section(s), and appendix may be considered. Facilitators may be used to clarify subject matter knowledge, but should not give opinions. One participant serves as the notetaker to document the groups input.

Table 2. Case Study Structure

Table with column headers Section and Discussion, with the respective lists of Study Description, Technical Description, Risk Analysis, Conclusion, Appendix, and Open Inquiry, Technical Analysis, Risk Assessment, Mitigation Strategy, Ad Lib. Source: Scott, Chaudhary, Bagade, 2024.

After small groups complete the questions, a reflective discussion with the facilitator and/or other small groups proceeds. The core questions to address are as follows.

- What was the most significant human subjects protections concern in your case study? Why? What policies and guidelines are associated with this?

- Are there gaps in existing policies and processes regarding the concerns? Is there ambiguity in the risks and potential harms? What more would you need to know about the technology?

- What mitigation strategies would you recommend? What are practical strategies to implement considering constraints of your institution? Consider data management, informed consent, researcher training, and physical safety.

The session concludes with an expert assessment of risk for the case studies as summarized in tables provided at the end of the session. A thorough explanation of the guidelines for study protocol review is then delivered with room for participant questions.

Case Study Sources

Each case study illustrates key challenges to XR research: (1) biodata and psychological stress [1], (2) haptics and brain stimulation [2], and (3) motion tracking and anonymization (unpublished). Researchers provided study protocols, informed consent documents, published works, and interviews to develop each case study.

Control of Physiological Signals Under Stress Using Biofeedback

Haptic Interface System Using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

VR Motion Data Privacy and Re-identification Risks

Director of Brain and Memory Care Lab, Bioengineering, Santa Clara University; Council Lead, MedXRSI

Former Chief of Staff, XRSI

Computer Science and Engineering, Santa Clara University