Gordon Young, Flint Expatriate

“Thanks for paying attention to Flint. What took you so long?” asks SCU Communication Senior Lecturer Gordon Young in his most recent article about Flint, Michigan, featured in Politico Magazine. Young, a fourth-generation Flint native, has a masters in journalism from the University of Missouri and also works as a freelance writer, where his work has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, Politico Magazine, SF Weekly, and the San Jose Mercury News.

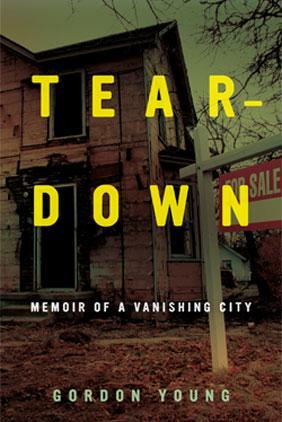

Over the last several years, Young has focused his writing on urban planning and economic development in cities. These “shrinking cities” as he calls them include places such as Flint, Detroit, and Cleveland. Shrinking cities are former industrial hubs that are now experiencing deindustrialization and depopulation due to shifting industries. In his book, “Teardown: Memoir of a Vanishing City", Young explains that urban planning in the U.S. has traditionally focused on development with the assumption that growth in city size and tax base are coupled, so that increased tax revenue can be used to accommodate the increasing population. In shrinking cities, however, the opposite occurs: decreasing populations means decreasing tax revenue, which leads to a lack of resources for cities and policy makers to address unprecedented, monumental issues.

Flint, Michigan, the birthplace of General Motors, had one of the highest per capita incomes of any U.S. city and a broad middle class in the late 1960s. By the 1970s, when Young was enjoying his childhood in the city, Flint began its steady decline. After reconnecting with his hometown in the early 2000s, Young realized that there was an untold history that needed to be shared. In 2007, he created the blog, Flint Expatriates to tell the story of how one of the most prosperous cities in the U.S. became a breeding ground for crime and perpetual crisis.

Over the last 30 years, as GM factories migrated from Flint to elsewhere, 70,000 GM employees were laid off and 100,000 people moved away entirely. The abandoned homes have attracted squatters, drug abusers, and have become a prime location for arson. Over this period, Flint’s murder and crime rates rose to one of the highest in the country. In reality, these factors have led to a much greater death toll than the water crisis, which Young argues is just the most recent calamity to face the troubled city. “I don’t mean to sound ungrateful, but I feel like people should have been reaching out to help about 30 years ago,” Young explains in the Politico article.

The real issue, according to Young, is Michigan’s current, small government policies, where less money is sent to cities that desperately need assistance. The lack of governmental support, paired with Flint’s own struggle to balance its budget while simultaneously attempting to fulfill its pension and healthcare obligations, puts the city in a problematic financial position. In response, the city made budget cuts, which led to sourcing cheaper water, but also included layoffs and cuts to the police force and fire departments. “That’s right, cops are laid off in one of America’s most dangerous cities,” Young says.

The crisis in Flint is not an isolated incident. Cities all over the country face similar problems while trying to adapt to demographic and economic changes that arise from shifting industries. To save Flint, citizens must look beyond changes in the municipal sphere, and demand change at higher levels of government. As American taxpayers, we are all stakeholders: crises like those unfolding in Flint end up costing more in emergency funding than it would have cost to invest in better infrastructure in the first place. Young stresses that in order to fully address the root of the issue in Flint - and prevent future catastrophes - there needs to be collaboration between federal, state, and local government. “Because if we don’t fix it this time, some other disaster will happen in the next 20 years, if not water, then some other calamity.”