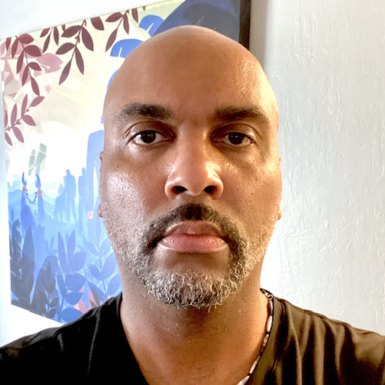

(Re)Imagining Past and Future: Afro-Indigenous Homecomings

In January 1880 the Rhode Island General Assembly declared my ancestors, the Narragansett people, extinct. In a rather curious way, state officials went about confirming who was and was not a “real Indian” by holding hearings, listening to testimony, and gathering documents for the purpose of telling those same people that their Nation was no longer. This land grab animated by genocidal violence and political chicanery used as a pretext the colonial logic that “racial mixing” amounted to extinction. In July I returned to Rhode Island to continue the journey of getting closer to my ancestors. From the moment Roger Williams “founded” Providence in 1636, my ancestors survived and resisted, and lived complex, adventurous lives. My third Great Grandpa James Alexander Monroe Hazard (1825-1908), who appears on the original Narragansett tribal roll (1880-1884), survived a career at sea in the arduous whaling industry, at one point suffering a terrible broken leg, which permanently altered his gait. His father James (1805-1870) who had served as Tribal Council President early in the 19th century, survived capture and enslavement in South Carolina also during a whaling voyage, according to testimony at the very hearings ahead of the state of Rhode Island declaring us extinct.

The younger James’s wife, Louisa Hazard (1843-1899), was employed for a time by writer Edward Everett Hale in South Kingstown. Laboring as a domestic servant, Louisa lived much of her adult life with or very near her mother Violet Ann Sands Hazard (1798-1903), who was born enslaved on Block Island to Aropa (1760-1801) and Benjamin Sands (1760-1852), both enslaved by Colonel Ned Sands. Driving up Commander Oliver Hazard Perry highway in South Kingstown after visiting with renowned wampum artisan Allen Hazard at his store, The Purple Shell, I spontaneously made a stop at Hale House.

Photo taken by author. The Purple Shell.

Charlestown, Rhode Island. July 5, 2025.

It was Saturday, July 5th, and I was the lone visitor. I walked the grounds that Louisa once had. Many photographs later I tried to imagine and (re)member Louisa’s time there, her triumphs and tragedies, her bond with her mom.

Photos taken by author. Historic Hale House.

Matunuck, South Kingstown, Rhode Island. July 5, 2025.

Granted her freedom under gradual emancipation at her 18th birthday, Violet left Block Island, eventually settling in Matunuck, South Kingstown, marrying Alexander Perry Hazard (1798-1875) (rumored to be the son of Dr. George Hazard and Sarah Perry, an enslaved Narragansett woman). Together the two amassed land holdings of 36 acres, and Violet became a highly respected nurse in the community. Ten years after Alex passed away, Violet lost their family home to a fire.

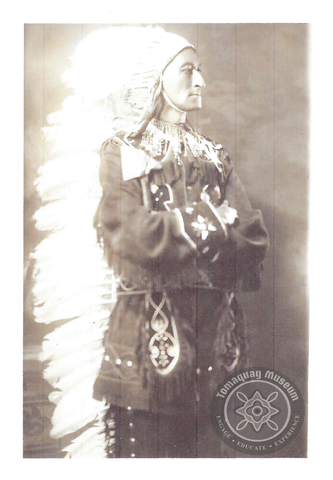

Louisa’s grandson, William Albert Hazard, served in the segregated 443rd Reserve Labor Battalion during World War I. Upon returning from the war, William married Elizabeth Harrison Michael in South Kingstown on May 5, 1920. Soon after my Grandpa William Jr. was born. Prior to this summer, I had identified Great Grandpa William and Great Grandma Elizabeth through census records. On this trip the Tomaquag Museum’s archival team confirmed for me the lines of descent of Elizabeth Michael; her mother Sarah Jane, her grandpa Brister, her uncle Chief Sunset (Chief Sachem during retribalization in the 1930s). I reimagined Great Grandma Elizabeth’s life and the meaning of this line of descent for those of us who came after.

Chief Sunset (Ed Michael). Miscellaneous Photographs, 1940s.

Tomaquag Museum Archives. Exeter, Rhode Island.

I began this journey by engaging secondary sources and attempting to decipher Grandpa William and Great Uncle Ernest’s World War II draft cards, Grandpa’s “race” as decided by a local draft official was “Indian,” his brother Ernest’s “Indian” and “Negro.”

It’s been over a month since I’ve returned to California. My son Luca has started Transitional Kinder, and this is the first I’ve written. In quiet moments, I return to the summer day I knelt before Grandma and Grandpa’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery, my right arm around Luca as he stands next to me.

Photo taken by author. Arlington National Cemetery.

Arlington, Virginia. July 12, 2025.

He recalls the humidity and lack of shade on the walk from the Welcome Center down to Section 25. I think of my attempt to compress time, to make memory, to remember the past. The many years of visits with Grandma at her Wyman Park apartment, I remember. With Grandpa, I have to imagine and reimagine him. My Aunt Casandra very recently shared with me that after the family PCS’d from Rhein Main to Ft. Meade in 1959, Grandpa consistently made his way up to Rhode Island for the August Meeting (Pow Wow). I wonder if Grandpa imagined those homecomings while on the battlefield in the Philippines. It’s no coincidence that Luca turns five this fall and I’m five years in on this journey. I cannot reimagine the future without reimagining the past. And the future is now.